![]()

Reveal Digital develops Open Access primary source collections from under-represented 20th-century voices of dissent, crowdfunded by libraries.

The content is curated and sourced from a wide array of libraries, museums, historical societies and individual collectors. The results are diverse thematic collections of scholarly value available to everyone everywhere.

Collections

Behind the Scenes of the Civil Rights Movements

Announced in April 2022, this new program focuses on unearthing and digitizing the histories of civil rights activism by the everyday citizens of Black, Latinx, Indigenous, and Asian American/Pacific Islander communities.

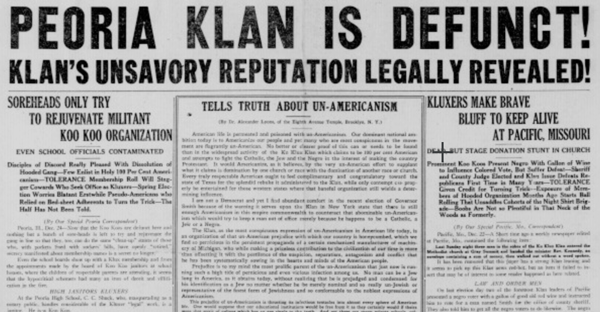

Learn moreDocumenting White Supremacy and its Opponents in the 1920s

To understand today’s version of American nationalism, we need to go back to the 1920s when the Klan re-emerged as a slick and successful recruiting and marketing engine that appealed to the fears and aspirations of middle-aged, middle-income, white Protestants in America. This project aims to assemble a comprehensive collection of Klan and other white nationalist newspapers alongside newspapers published by Catholic, African-American, and Jewish organizations to counter the narrative of hate and bigotry.

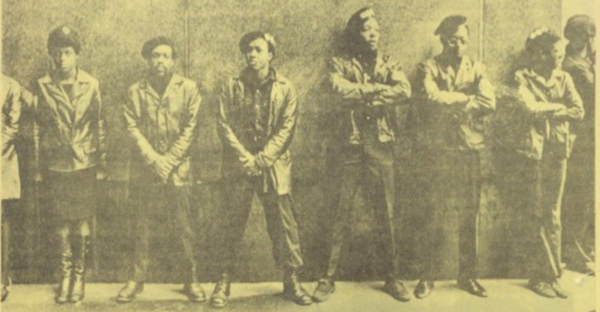

Learn moreBlack Periodicals: From the Great Migration through Black Power

The final collection for Diversity & Dissent will include periodicals that depict the various political, literary, and cultural forms that Black Americans used to advance their vision in the ongoing struggle for liberation and dignity.

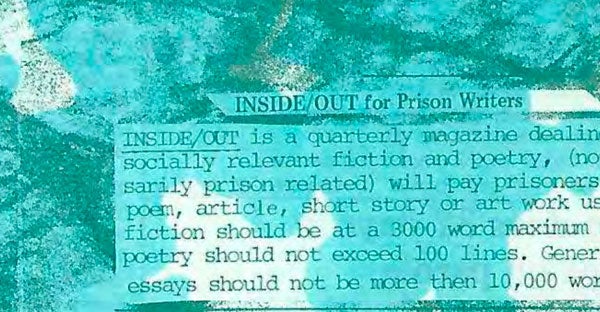

Learn moreAmerican Prison Newspapers

This collection of newspapers produced by citizens who have been incarcerated will help readers learn about the prison experience through the voices of those who have lived it.

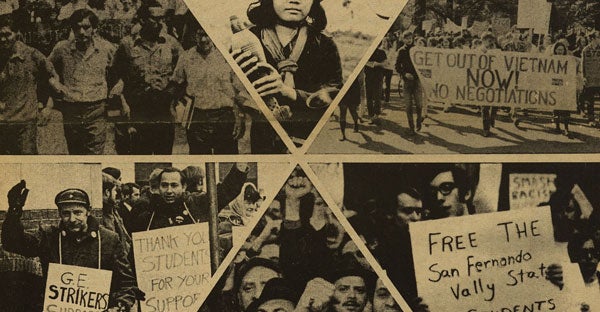

Learn moreStudent Activism

The study of activism on campus helps us understand the history of protest movements and to inform our understanding of today’s student activism.

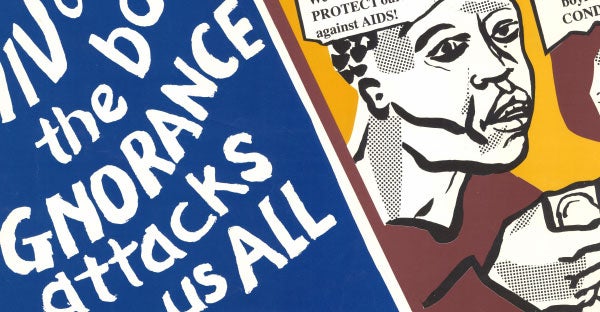

Learn moreHIV, AIDS & the Arts

An internationally scoped collection of primary sources documenting the artistic response to the AIDS epidemic.

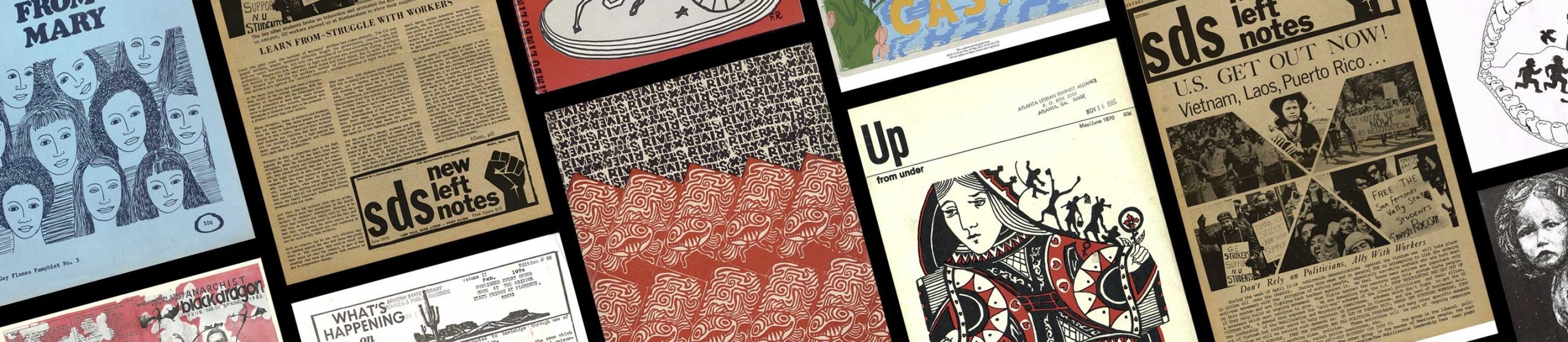

Learn moreIndependent Voices

The flood of alternative press publications in the 1960s expressed the upsurge of dissent and aspiration of American youth that continued for two decades. Feminists, dissident GIs, campus radicals and the New Left, Native Americans, anti-war activists, Black Power advocates, Latinos, and members of the LGBT communities all began to publish newspapers, periodicals, and literary magazines (little magazines). All of these groups found their voices in the alternative press.

The collection is now complete and freely open thanks to the financial support provided by the project’s funding libraries.

Learn more